Chapter One - Fortune Favors the Bold

A wooden keel will plow through water whatever hand lies upon the helm. At its awkward birth, the hull lumbers from the cumbersome staging of the shipyard down into the waiting salted bath. The ship’s bow splits the sea into a womb as the planks swell against the liquid embrace of the sea. Wrapped from stem to stern in the brine of its birth, the ship never leaves its true mother. She envelopes the craft however swift or slowly it may sail. When it moves, it knows her hand, however peacefully she may cradle or angrily discipline her charge. And once the craft’s days are done, she reaches up in the last, inescapable embrace, swallowing every beam, every timber, every canvas sail and human soul into the long dark sleep of the deep. Whatever human hand calls itself “Master” and steers that ship over the broad waters of the earth, the ship knows its true, beautiful and terrible parent - the true master of the voyage. Human deeds, good or ill, the sweat of human toil and the blood of life soaking those planks may ennoble a cause or populate the pages of history, but they are of little concern to those long boards as they groan against the sea and forever plow forward towards the next birth.

And so it is that when two step-siblings, ships different nations on the same great ocean, clash under the midday sun, the sea chooses no sides. They are, after all, loved no more or less than one another. If one ship is to no more feel the crisp breath of the zephyr on its white sheeted sails, straining the tackle and driving the prow to voyage across ocean’s kingdom, it is no loss. A mother always longs for her children to return. The sea is no different, so she watches and waits.

In the Indian Ocean she watched, one day, as two of her children quarreled in the sun. The heavy, humid salt air was stirred by a crisp breeze. Had she been that breeze she would have smelled the burning powder in the air, heard the shouts of human voices and felt the blasts of percussion as the volleys roared out from the guns. Up in the unencumbered air lay a test of captains and of crew, each side riding clear of cannon shot, yet struggling with sail and posturing to gain a lead on the other. They strove to cut in across their opponent’s path, firing a full broadside into the enemy’s prow. It was still early in the game, but it carried on into the afternoon, the two ships reeling in and out from one another, here and there exchanging fire.

Neither side was trying to flee. As the ships drew close the crews would exchange taunts in disparate languages. Some would utter curses or dare their enemy to come closer, brandishing muskets and cutlasses. Others kept feverishly working sail and cannon, knowing the slightest advantage could make or break the engagement. The crews, as a whole, were not disciplined but the sea was their life. Though they did not possess the ordered maneuvers of the English navy, they worked with the feverish passion of men who knew the face of the specter of death. The flags had begun as the national colors of Great Britain and Spain, but when the ships grew close enough to parley the English brig ran up the bloody red flag of piracy, signaling no quarter. The Spanish flag was just as quickly struck, and in its place flew a tattered black sheet with a curved white cutlass blazoned across its face. Both sides knew now, as both had suspected, that this was a battle between sea dogs.

Whereas many European pirates would join in league with one another, the Spanish ship appeared to be manned primarily by Moors, probably deserters from the navy of India’s Great Mogul. The ship itself was a two hundred ton caravel that did, in fact, appear to be of Spanish design. The name on the stern read Conception. The brig flying the red flag was named Decision, and was manned by a mix of sailors from England and the American colonies. When they saw the colors of the Moorish crew rise up they cheered as one with battle lust. They had been cruising the Arabian coast for pilgrims headed home from Mecca, but had been unsuccessful in spotting a quarry after two long months. The voyage was looking worse and worse as the season drew to a close, until, at last, they saw the Arab ship on the horizon.

Far above their heads a gull circled, watching the battle below. Every so often a burst of cannon fire would erupt below and a plume of white smoke would issue from the ship that fired. Curious, the bird rode the breeze for a while, listening to the distant shouts and the louder reports of the ships’ guns. After a while it grew uninterested, then wheeled and flew north, back to its fishing grounds. Far below, in the bow of the Decision, a young cabin boy watched the bird and dreamed that he, too, could fly far away from this scene.

His name was Ben Christian. He had been taken from his father’s fishing sloop off the coast of Nova Scotia some six months ago and pressed into to service by the pirates. It was a black day he wished he could forget. Nights he prayed for deliverance and prayed to wake up, as if from a dream. It was a life of violence and chaos. The violence, oddly enough, did not disturb him as much as the chaos. In New England there had been violence. He had grown up witnessing the cruel punishments of the witch trials in Salem. He had seen a hanging in Boston one day. On another occasion his father’s sloop put into Plymouth and he saw the severed head of King Philip, leader of the Wampanoag indian revolt that truly threatened the survival of the early colonies. The trophy was mounted and rotting on a pike at the entrance to the plantation, to warn and horrify local natives into submission. It had disturbed him, but in some way it had its place in the keeping of order and the protection of society. Order was the thing he missed most, so he created it as best he could by carrying out his duties on board with a sense of responsibility, regardless of the others around him. Many crewmembers were drunks or slackers. It was hard living as a prisoner, facing their daily taunting, doing much of their work and always running that day over and over in his mind, wishing for a different outcome. It was no use, however. An explosion of splinters near his head brought Ben back once more into the present.

The brig was manned with sixteen, twenty-pound cannons and it also mounted a pair of light swivel guns, one fore and one aft. Ben was running powder from the magazine below to the gunners toward the bow. He had refused to join the crew when asked repeatedly after his kidnapping, so he was not allowed to carry a musket or a pistol, but he did have his sailor’s knife tucked in his shirt. He had no choice but to serve as a powder monkey. He learned very quickly that any argument with the crew would bring a swift and vicious beating. An argument with the captain or Hendrickson, his quartermaster, could bring worse.

There was a very varied assortment of men on board the ship. Most came from England and Wales, and seemed to have deserted from either the King’s Navy or been picked up loafing in some Caribbean port. There were many from New England, as well, though Ben knew none save one of his neighbors, who was also taken the day they took Ben. His name was Gabriel Ellis, and he had tried to watch over Ben as much as possible, but a fever took him as they passed through the South Atlantic and headed for the Cape Horn. He grew too sick to move, lingered on for a week and was buried at sea shortly before they reached Madagascar.

And so, Ben found himself alone in a crew of cutthroats he would not join. Pressed into service but unrewarded for it, he served solely to escape punishment. Desperately hoping for some escape or to be freed, he was yet doubtful that it would ever happen. He managed to avoid trouble with most of the crew, and seemed to garner some respect from Hendrickson for his work ethic. There was one man, however, who he feared and avoided whenever he could. He was an older pirate named Gilliam. Gilliam was as evil a man as Ben had ever met. He beat the boy on many occasions and mocked him to entertain the crew. Two months ago they had taken a small and disappointing prize towards dusk one day. As the pirates searched the merchant vessel, one of the captured crew began to pray out loud. Gilliam laughed at the man and chided him “Yer maker should’ve saved ye afore we boarded. Damn ye for yer prayin, it’s curses what a man utters on my watch. Maybe yer God don’t hear so well, what with all the ruckus. Why don’t ye get a little closer and maybe then he’ll hear you, if he don’t damn you to hell...” And with that he pulled a long pistol from his waist and shot the man in the head. Ben knew then that he was as forsaken a soul as there ever was, and Gilliam was truly to be feared at all times.

A ship is a small place, and Ben could hardly avoid Gilliam forever. Even now, as the battle raged on, Ben found himself running powder to Gilliam, who manned the fore swivel gun. The gun was most effective at peppering an opposing ship’s crew with grapeshot, firing down over the gunwale and clearing the decks before a boarding was attempted. The caravel rode higher in the water than the brig, so the gun’s effectiveness was limited, but Gilliam knew how to use it and took more than a few men down from the rigging. In the last exchange the Moors had taken out the brig’s mizzen mast with a well placed ball. The deck was littered with sail and ropes and beams, and the ship was floundering without the sheet it needed to maneuver. The Arabs had rained shot in for several more exchanges, and clearly had the advantage. They came close now, preparing to toss grappling hooks and pull in to board the Decision, and as they did Gilliam fired into the jeering masses.

He was a vicious bastard, but he was a brave and vicious bastard. Moreover, he had been living this life for years, and it was no accident that he had lived so long. Gilliam knew how to fight and he knew the only other option was to die. As the Conception grew close he read the fear in some of his fellow crew’s faces and swore oath upon oath that the first to falter would feel his blade in their backs. There was no room for cowardice here, and he would not stomach it from anyone.

The ships came close and Gilliam fired another volley into the caravel. Muskets and cannons fired all around, and chaos began to rule the scene. Grappling hooks were tossed over and the ships crashed together. The smell of burning sail and gunpowder filled the air and stung Ben’s nostrils. His heart beat at a furious pace. He saw the Moors with pikes and swords rushing to board. He saw them toss missiles into the center of the deck. Shouts erupted and some took cover as grenades went off. Boarding planks were thrown into position and the men around Ben braced for the fight. Many had pikes and they met the oncoming Moors point to point. Towards the aft of the brig Ben saw the captain and the quartermaster rallying a handful of men with muskets. They brought their guns to bear on the leading boarders, filled them with shot and fell back to the helm. Snipers in the rigging on both ships fired down on the decks. Gilliam was a fool to stand so exposed, but he risked the fire from above to get in one more shot from the swivel gun as the Moors pushed through the English pikes. Men were falling everywhere, and the enemy seemed to be making a big push toward the captain.

Gilliam’s gamble paid off and he was able to take out three men just as they attempted to cross from the caravel onto the brig. A shout came up among the Moors, though, and they rallied back into the fray, led by an enormous Lascar with a tattooed face. He brandished a pike in one hand and a curved scimitar in the other. He had seen Gilliam’s defense and recognized an opponent that had to be met quickly. As he landed on the deck two New Englanders charged to meet him, but he cut one down and pinned the other to the broken mizzen with his pike. Gilliam rose to meet the challenge, cutlass in hand.

Ben watched as the two rushed at each other. There was no hesitation as they met, clashing steel on steel. Filled with fear, Ben crouched and watched as the two opponents desperately fought to kill one another. Gilliam and Ben were alone in the bow now, save for the bodies of the fallen. In the stern of the ship the Captain and quartermaster had fallen back with a group of men and were still holding off the onslaught. The great Lascar shouted in Arabic and those who had boarded with him joined the other Moors fighting their way towards the captain.

It was sudden when Gilliam was killed. More precisely, the blow was sudden. The Lascar used his size, strength and speed to knock one of Gilliam’s parrying blows wide, and then in an instant to thrust up and into his stomach. Ten years earlier he would have been able to stop the blow, but age wears on a man’s reflexes. He had sometimes wondered when this moment would come, but he was not one to accept it. With great effort he cried out for help, but the Lascar did not withdraw the blade and instead proceeded to raise him off the ground with it. “Aiigh, boy – damn you – help me…” cried Gilliam, and for a second longer Ben crouched paralyzed. But it was only that second that it took for him to process many thoughts at once. In that moment he knew he had to help this man, for honor’s sake and for his own survival. The Lascar would turn on him next, and he only had a vanishing moment to act. He grabbed a pike from the deck and charged at the giant, and for his last painful moment the dying pirate smiled. “Damn the moor to hell, boy…”

The Lascar grabbed the shaft of the oncoming pike with one hand, dropped the scimitar that was still impaled in Gilliam, and knocked Ben to the deck with a crushing punch. Ben fell in a heap next to Gilliam’s body, but he was not fazed. Deliberately and quickly he rolled closer to Gilliam and shoved his right hand under his blood soaked body. The Lascar changed hands with the pike and poised himself to lance Ben when the boy rolled away from Gilliam. In his hand was Gilliam’s pistol, and without hesitation he pulled the trigger and put a hole through the Lascar’s shoulder. The giant was blown back and down to the deck himself, but he was not dead. He used his legs and one good arm to hurl himself across the deck onto the boy.

Ben felt the suffocating weight of the Lascar pinning him to the deck. He smelled the sweat and smoke and blood of the battle and he struggled to move some part of him that could defend himself. He felt hands of steel clamping around his neck and saw the wild look in the painted devil’s eyes. There had been moments during his imprisonment when he thought death would be a comfort, but now that the prospect faced him he understood, as Gilliam had understood, that one must fight well or die. He felt a frenzied panic which became a strength to him, and in that panic he found his sailor’s knife, still tucked into the folds of his shirt. For all of his strength and skill the Lascar didn’t have a chance.

Ben, shaking, stood slowly on the deck, hands wet with blood. Looking towards the noise of the battle he saw two dozen moors fighting their way toward the faltering forces of the captain. In a moment he knew what he must do. He pulled the scimitar from Gilliam’s body and stood, feet spread wide, over the Lascar.

The captain had seen Gilliam fall and had begun to lose hope. Hendrickson, the quartermaster, fought bravely beside him along with twelve other good men, but the odds were fading rapidly. He had three pistols on his person and had fired two of them already. It seemed only a matter of time before they were overwhelmed. No quarter would be given. He had drawn his last pistol, along with his cutlass, for one last foray, when he heard a blast from the front of the ship. Four of the moors fell instantly to a close range volley from the bow swivel gun. The moors recoiled in horror, but it was not solely the sight of Ben wielding the gun that terrified them. As they turned to see where the blast had come from, he let go the gun and raised, in one hand, the bloody, tattooed head of the Lascar high for all to see. Their captain was dead, and with him the whole heroic power he had brandished. They floundered, and in seconds three more fell to the crew of the Decision. The rest scattered or froze on the deck. Ben picked up the reloaded pistol and approached from the bow as the captain ordered quarter to be given. It had been a bloody battle, and they would need more crew.

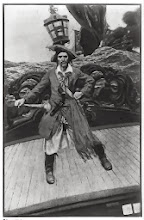

As evening fell the sky was a brilliant crimson, mixed with gold. Ben sat on the deck of the Conception and drank the beer he had been offered. All told about a score of the crew had survived, as well as the captain and Hendrickson. They took six moors to replace some of the dead. The brig was abandoned and burned to the waterline. Anything worth keeping was moved to the caravel. The ship still reeked of gunpowder, but it also smelled of the spices they carried in her hold. It was a good prize. On deck, Ben had been given a new pair of clothes taken off the captured ship. He now wore a silk sash and kept Gilliam’s pistol and his own knife in it. Under his hammock he kept the Lascar’s scimitar, though it was too big for him. As they drank and sang to celebrate the victory, hard fought though it was, the captain once more approached him. “You’re a stubborn boy, but you fight like a man. I’ll ask you again, will you go on the account with us?”

It was death to agree, at least in the courts of civilization. Caught here, between the devil and the deep blue sea, choices were less black and white. He missed his father, and his brothers, but here he felt something stir that he had not felt before. In the light of the moon and the ship’s lantern he took a quill and made his mark on the ship’s articles. When he was done he prayed, quietly, to himself. Then he sat for a bit with his beer. Talk turned to an island where the native girls would comfort a sailor in any way for a copper nail or some beads. The captain disappeared and returned with a bag of coins. “Here’s your share, boy.”

Many fathoms beneath them, the sea gathered the the charred hulk of the Decision and crushed it to her breast. In the darkening gloom of the deep she welcomed them all: the Welshmen, Moors and Gilliam himself, riding in the bow like some ghastly, spectral figurehead, racing the headless torso of the Lascar to the depths of her embrace, and to hell below.